5 Life-Changing Lessons From Comic Book Heroes About Growth After Trauma

December 05, 2022

Comics fascinate us. From traditional comic books to modern action movies, they help us examine the relationship between good and evil. They tell extraordinary stories reflected in our ordinary lives. And, perhaps most powerfully, comics address how to face difficult circumstances and find growth through trauma.

Why is growth through trauma a typical theme in comics? Unfortunately, trauma is a common human experience and in any hero’s journey, overcoming obstacles and traumas is generally part of what makes someone heroic. Traumatic events found in comics include natural disasters, terrible accidents, wars, violence, death, loss, and other adversities. But those traumatic experiences aren’t just found in comics; they reflect the common traumas and experiences of our real lives: more than 70% of people experience a trauma in their life, but trauma is often taboo to discuss, we don’t realize how common it is.

Here are 5 life-changing lessons from comics about growth after trauma.

Post-traumatic growth in comics

1. It’s ok to be vulnerable

2. Trauma shows up in expected ways

3. It’s normal to feel “negative” emotions

4. Trauma can be complicated, have empathy

5. Go easy on yourself

Post-traumatic growth in comics

Trauma is so central to both life and heroism that we’ve written this experience into our comic books. Conversely, image-heavy comic books and animated movies then shape our perspective of the human experience from a young age before we can even read. As adults, many still turn to comic characters as metaphors for how we might face and even grow from trauma.. Characters who are able to effectively channel their traumas become heroes like Batman. Those with similar traumas, but who process them in unhealthy ways, become villains like the Joker or the Riddler. Let’s learn about the psychology behind comic heroes and trauma.

A hero’s 5 steps toward post-traumatic growth?

Comic heroes typically have experienced what Richard Tedeschi and Lawrence Calhoun call “post-traumatic growth.” These psychotherapists coined the term to describe a phenomenon they noticed in their research: some people actually report a positive life transformation and increased well-being after a traumatic event.

Typically, heroes have taken the steps that scientific research suggests directly lead to post traumatic growth. These steps are:

Learning that growth after trauma is actually possible

Developing emotional regulation and mindfulness skills

Sharing your story in a safe space

Building a healthy life narrative with new goals and dreams

Doing acts of service in the area of your pain

While all of these steps are often part of a hero’s journey through trauma, the last step is the most obvious hallmark of our comic superheroes–they turn their pain into acts of service. It’s interesting to note that acts of service are not only good for others, they are good for our own brains and psychological well-being.

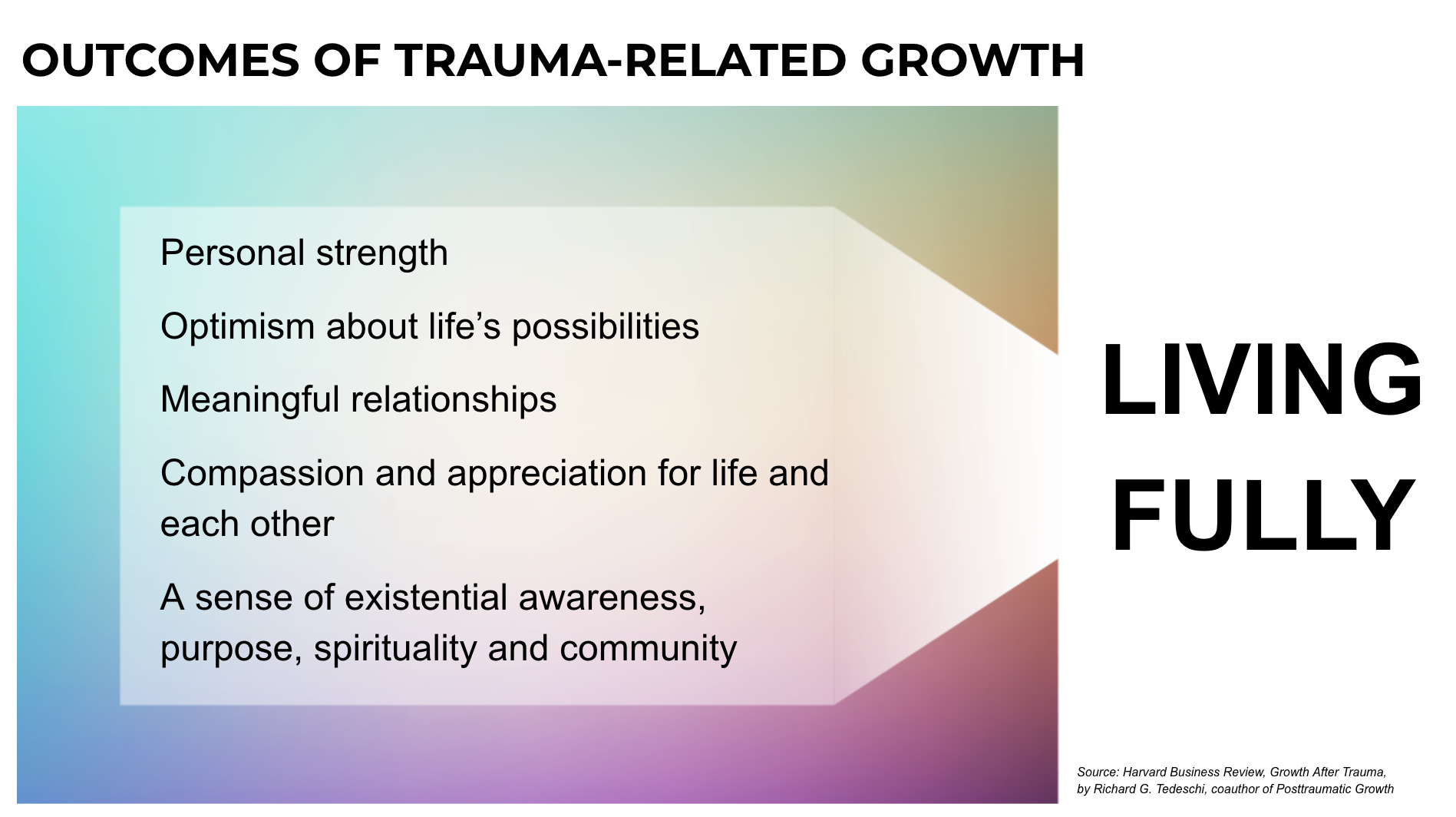

What are the heroic outcomes of post-traumatic growth?

Sure enough, post-traumatic growth research also suggests that doing these steps leads to a set of positive personal outcomes we often associate with our heroes:

Personal Strength - Increased belief in yourself to overcome challenges and difficulties.

Optimism - Openness to new opportunities and ideas leading to positive changes.

Strong Relationships - Strengthened bonds between you and people you know.

Deep Appreciation - Heightened gratitude in daily life for people and things.

Spiritual Depth - Deepened sense of awareness, purpose, spirituality, and community.

To explore more deeply about how the concept of growth after trauma is treated in comics, we draw upon a fascinating online event. At Reimagine, we hosted a virtual panel discussion exploring the Superhero’s Journey, featuring speakers with a special interest at the intersection of comics and loss. Each speaker presents lessons about trauma they’ve learned from comics. Below is a synopsis of those main lessons.

1. It’s ok to be vulnerable

Dr. Jill Harrington, moderator on the Superhero’s Journey, shares her own incredible real-life origin story detailing how Bob Kane, the original co-creator of Batman, reached out to her as a young child. When her sister was in the hospital with a life-threatening illness, Kane’s sister was the attending nurse. Hearing about the family situation, Kane sent a set of comic-related cards to comfort Jill.

Those comic cards helped Jill process her feelings of isolation during a difficult time, which launched Dr. Harrington’s comic book obsession. Wonder Woman soon became her lifelong role model. Part of Harrington’s learning is that while we think of comic heroes as strong and impressive, she points out “that’s not saying that a hero has a clean path.” Heroes have imperfections, too, and that is important to acknowledge. Wonder Woman, for example, carries a shield and a sword to protect her from her vulnerabilities.

The challenging emotions of her sister’s medical battle led Harrington to become a clinical psychologist and publish a book called Superhero Grief. Today, Dr. Harrington works as a thanatologist, a professional in the study of death, grief, loss, and bereavement. She works with cancer patients using superhero narratives, emphasizing that comic book stories can destigmatize human struggles. If heroes can have vulnerabilities, so can we.

2. Trauma shows up in unexpected ways

For panelist Joyal Mulheron, now a grief specialist, her daughter’s death informed her approach to grieving, loss, and bereavement. She sees the ripple effects of grief and trauma. “The death of a loved one isn’t simply just a personal tragedy,” she says.

Mulheron says exposure to death or trauma is like the radiated spider bite that turned Peter Parker into Spider-Man. First, there is the intense shock to deal with. Then, as a result of that bite or “challenging experience,” unexpected transformations begin to occur–it changes you in challenging ways, and it can also lead to newfound heroism.

Mulheron cautions, however, that currently our health and community support systems aren’t well configured to support people in experiencing growth after trauma. Therefore, just acknowledging or being with the trauma is a big win.

Mulheron’s work for the last fifteen years has focused on legislating better support in the US for the bereaved. As a political advisor to multiple White House administrations, her work expanded bereavement leave under the Family Medical Leave Act (1993). She also influenced the Center for Disease Control (CDC) language to capture data and provide tools to state governments for bereavement research. Her hope is to take her traumatic experience of her daughter’s death and, like Spider-Man, cast nets to cushion other people when they fall.

3. It’s normal to feel “negative” emotions

Dr. Tashel Bordere, thanatologist and Assistant Professor of Human Development & Family Science at the University of Missouri, uses Black Panther characters to describe traumatic growth experiences in marginalized communities. She highlights how privilege and oppression affect who is allowed to feel strong emotions and who is repressed by society.

Erik Killmonger is the villain of the Black Panther’s hero story. Black Panther comes from a wealthy background with supportive parents. Erik Killmonger was abandoned after his father died. Both characters endure violence, but Erik experiences multiple losses and processes his grief through anger.

Dr. Bordere says Erik represents many of the Black male youth she has worked with through her research. “They’re having to repress a whole lot of feelings just to survive,” she says. “We see that with Erik, he was penalized for having normal grief reactions. It’s normal to be angry. It’s normal to be sad…Not condoning his violence, but if you don’t give a person a way to [process emotions], they’re going to externalize” their trauma in hurtful ways.

Dr. Bordere calls this suffocated grief. The concept describes how marginalized people (“largely Black populations, but it applies to all'') are penalized by society for normal reactions. A potential hero can become a villain when not given the tools or support to experience post-traumatic growth. Erik Killmonger is a cautionary tale of the limit of our human capacity to repress trauma. How might we externalize or process our trauma in healthy ways, so we can become the heroes of our own lives?

4. Trauma can be complicated, have empathy

Marvel comic author Yona Harvey provides further insight into growth after trauma through the Black Panther character of Zenzi. As co-author of two Marvel series (World of Wakanda and the Black Panther and the Crew), Harvey built on Zenzi’s backstory to develop this comic character’s story arc even further.

Harvey says most readers label Zenzi a terrorist. After all, she sets off bombs in Wakanda and harms the Black Panther’s mother. But Harvey points out that when you stop short of labeling someone a villain, you can begin to see the true complexity of their journey and reframe how you see that person.

To explain, Harvey draws upon the real-life history of Winnie Mandela, anti-apartheid activist and second wife of Nelson Mandela. Harvey points out that Winnie Mandela engaged in violent action and even spent time in prison. Some might label her a criminal. But when you consider the regime of racial segregation policies that she was fighting against, her drastic measures can be viewed in a different light. Violence was met with violence, and–in context–perhaps that’s not “bad.” “I always see her as just a complicated figure; I don’t like to see her get dismissed,” says Harvey.

Her real-life geopolitical studies helped Harvey understand and paint Zenzi as equally complicated. Harvey points out that to empathize, we must “unlock a space of imperfection and complication around characters” both in comics and in real life.

5. Go easy on yourself

Throughout the Superhero’s Journey discussion, “space” was a common theme…and not outer space! Allowing space for one’s self to grieve and process is key to moving forward from loss towards growth. We don’t need to be strong all the time. Dr. Harrington points out, “the strongest thing on earth is a spider’s web;” Spider-Man’s powers come from being both strong and delicate at the same time.

Joyal Mulheron explains that in her work she avoids using the words “healing”, “resilience,” and “closure.” She feels these words put pressure on the individual to take certain actions. Instead, people need space to be.

Dr. Bordere also cautions against focusing on positive outcomes too early. “We shouldn’t have to grow through some awful experience,” she says. Though we can learn from pain, it doesn’t mean pain is good–rather, it’s a part of life. People need “space to not have to channel it, space to not have to turn it into something” before growth can come.

Dr. Bordere points out that after being given space, Erik Killmonger experiences growth at the end of his journey by bonding with his cousin. “He was able to connect with somebody in his life and talk about his grief and his pain.” If comic book characters need space to open up, then perhaps we do, too.

Post-traumatic growth is possible

As we’ve seen, knowing that growth after trauma is possible is the first step towards progress. Along the way, don’t forget that it’s ok to admit your vulnerabilities, acknowledge your emotions, accept that trauma isn’t simple, and give yourself space to process. Post-traumatic growth is not a goal but a journey. Want to stay in the know about upcoming events and the inspiring ways people are navigating adversity? Visit us at Reimagine and click “Stay Connected” to receive updates.